Gallery: A love letter to the planet

Sebastião Salgado spent eight years traveling the world to photograph humans, animals and nature in their native glory. See eight of his breathtaking images.

Continue reading

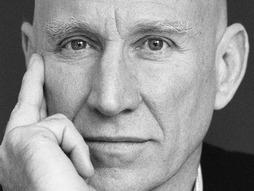

A gold miner in Serra Pelada, Brazil; a Siberian Nenet tribe that lives in -35°C temperatures; a Namibian gemsbok antelope. These are just a few of the subjects from Sebastião Salgado’s immense collection of work devoted to the world’s most dispossessed and unknown.

Brazilian-born Salgado, who shoots only using Kodak film, is known for his incredibly long-term projects, which require extensive travel and extreme lifestyle changes. Workers took seven years to complete and contained images of manual laborers from 26 countries, while Migrations took six years in 43 different countries on all seven continents. Most recently Salgado completed Genesis, an ambitious eight-year project that spanned 30 trips to the world’s most pristine territories, land untouched by technology and modern life. Among Salgado’s many travels for Genesis was a two-month hike through Ethiopia, spanning 500 miles with 18 pack donkeys and their riders. In the words of Brett Abbott, a Getty Museum curator, Salgado’s approach can only be described as “epic.”

“Other photojournalists go in and out for a day. Sebastião goes and lives with his subjects for weeks before he even takes a picture.” — Peter Fetterman, in The New York Times

Sebastião Salgado spent eight years traveling the world to photograph humans, animals and nature in their native glory. See eight of his breathtaking images.

Continue readingAsk photojournalists to name a peer they admire, and Sebastião Salgado’s name is sure to crop up. The Brazilian is renowned for the long-term projects he undertakes, devoting years at a time to documenting the story of a particular people or the evolution of a certain place. As he describes in the talk he gave […]

Continue readingI’ll never forget the first images of Sebastião Salgado’s that I ever saw. At the time, I was just getting into photography, and his images of the mines of Serra Pelada struck me as otherworldly, possessing a power that I had never seen in a photo before (or, if I’m honest, since). In the twenty […]

Continue reading